Summer. Lazy days when no alarm clock heralded wake-up time (with Emperor Gene Nelson on KYA, before FM was a thing).

We bicycled to the shopping center; few houses had been built along Alameda in Atherton. Mostly small ranches, a few horses grazing, our bike book baskets filled with carrots for them, and our lunches packed for impromptu picnics in someone’s pasture.

Tackle basketball was def a thing in our driveway court waiting for dusk to settle, then Tag til after sundown. Older kids TPed houses when younger ones were called inside. “Mrs. Inseth needs to borrow a couple of rolls, Mom.” Did Mom ever wonder why Isabel never repaid them?Did Isabel wonder why my mom didn’t either? Gary and I laughed, mischievous collaborators . Between the two moms we’d score a four pack. Often enough that I’m surprised neither provided the other with a gastroenterology referral.

We carefully chose bathing suits for summer trips to Berryessa, my HS bestie and me. We washed our hair with Clairol Herbal Essence in the glassy lake, then disturbed the calm with a blast across the water in a speedboat for a speed dry. First job was at the local drugstore, where the ice cream scoops were 15 cents and lunch was a tuna melt at the fountain.

Late August brought the heat and the boredom, essential ingredients in a proper summer. It was time to think about school again. Catholic school wool plaid skirts of green and gray in hot sticky JCPenney fitting rooms. Corona cigar boxes filled with new pencils and a faux tortoise shell fountain pen. Schaefer ink cartridges ready to do battle with my left-handed smear. There were new, stiff, blister-causing saddle shoes, always bright white with orange crepe soles. Couldn’t wait to ditch those, just in time for their fashion comeback in public high school. (There was a slight switch up though, tan and navy, with — orange crepe soles.)

High school brought new clothes and free dress. Bay Area summer starts in September, right about now. You gotta wait, it’s too hot to wear that dreamy new, pink cashmere sweater. I once took a chance. Turned out to be a 101° day.

Oops.

These were summers of my childhood.

A complete summer required completing all rituals. There can be no return to school without discharging the entire checklist. The first strains of “I’m bored. There’s nothing to do,” must be heard from a child before a PB&J can make its way onto sliced wheat, and into a brown bag. Aren’t we bound to a grocery store trek? Which chip assortment will get the place of honor in a September back-to-school lunch bag? Then there’s the first (and maybe only) prized treat of the school year, a Hostess hand pie, apple or berry, with a crackly glaze on its half-moon crust.

No summer is truly over until all siblings begin purposely aggravating the others because there’s nothing better to do. “I’m telling Mom,” “Mom, he’s looking at me!” An exasperated mother must blow a fuse and holler to her neighbor over a redwood fence, “I’ll be so glad when school starts! I can’t take the arguing anymore.”

Not on a bright, mid August day with summer in full swing should a kid be plucked from fun for confinement in a classroom. No books need be cracked while one more road trip and hotel pool beckons, no heavy backpacks slung across slumped seven-year-old shoulders before September shows on an old-fashioned paper calendar. With the sun still deciding if it’s set, daylight not fully dimmed, no bed should call a kid on break.

In the midst of squashed late summer rituals eschewed by adults with bad ideas, and the premature reinstatement of school, I hear distant squeals of summer joy, stifled. Summer demands a proper last hurrah. It is the rightful heir to the final few weeks of school-free days and late bedtimes.

Summer has been snatched away before Labor Day. A complete August violation.

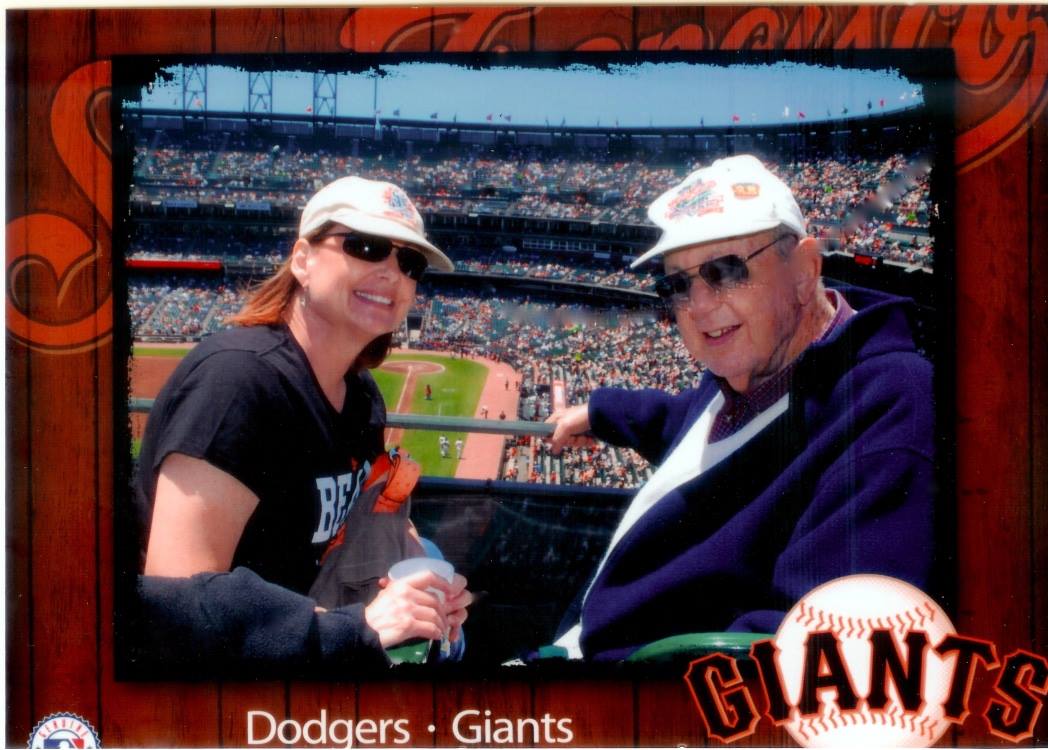

you go with it. I grew up there and never missed that parade. Each year my dad took us downtown to see the marching bands, baton twirlers, mounted regiments, floats, veterans, scouts, and color guards strut proudly down Main Street and Broadway as we wriggled through the crowd for a better view. As long as my grandmother lived in Redwood City, we stopped at her place to take her with us.

you go with it. I grew up there and never missed that parade. Each year my dad took us downtown to see the marching bands, baton twirlers, mounted regiments, floats, veterans, scouts, and color guards strut proudly down Main Street and Broadway as we wriggled through the crowd for a better view. As long as my grandmother lived in Redwood City, we stopped at her place to take her with us.

No doubt this daughter of eastern European emigre, born the year after the big quake of ’06, raised in an orphanage, having survived the Great Depression and two world wars, understood better than I ever will the meaning of the day. She understood the depth of courage and decency, resilience and devotion to freedom that parade represented, and all the parades throughout the USA, in cities and townships, villages and suburbs. On floats and in wagons. Fancy and not.

No doubt this daughter of eastern European emigre, born the year after the big quake of ’06, raised in an orphanage, having survived the Great Depression and two world wars, understood better than I ever will the meaning of the day. She understood the depth of courage and decency, resilience and devotion to freedom that parade represented, and all the parades throughout the USA, in cities and townships, villages and suburbs. On floats and in wagons. Fancy and not.

and compact, hairy golden arms and chest, a gray-blonde comb-over, light skin and blue eyes. His stature was exactly what one would expect of an older Italian gentleman while his coloring was the opposite. One of his jobs was to ride herd on the grandchildren and keep order in the yard. With our unwanted help horse beans grew in the daisy and gladiolus beds, and avocado trees (launched from seeds on the kitchen window sill) sprouted almost anywhere. None of this made Grandpa happy.

and compact, hairy golden arms and chest, a gray-blonde comb-over, light skin and blue eyes. His stature was exactly what one would expect of an older Italian gentleman while his coloring was the opposite. One of his jobs was to ride herd on the grandchildren and keep order in the yard. With our unwanted help horse beans grew in the daisy and gladiolus beds, and avocado trees (launched from seeds on the kitchen window sill) sprouted almost anywhere. None of this made Grandpa happy. backed up to a thick hedge that created a border between my grandparents’ yard and the Bonaccorsi’s, next door. Sometimes the vines in the hedge played a weaving game, tangling with other greenery then poking through into the lath house. Pink and red climbing roses grew at its sides among blue hydrangea bushes. Nature provided all the adornment needed against the crisp white back drop of the lath house.

backed up to a thick hedge that created a border between my grandparents’ yard and the Bonaccorsi’s, next door. Sometimes the vines in the hedge played a weaving game, tangling with other greenery then poking through into the lath house. Pink and red climbing roses grew at its sides among blue hydrangea bushes. Nature provided all the adornment needed against the crisp white back drop of the lath house. length on each side. During the winter the table was covered with newspapers and screened racks for drying walnuts and fava beans in their variegated pods. As warm summer days slipped into chilly late autumn, walnuts dropped from the orchard trees. The nuts spent winter drying in the lath house and those not carried away by the squirrels made their way inside for shelling, sorting and storing.

length on each side. During the winter the table was covered with newspapers and screened racks for drying walnuts and fava beans in their variegated pods. As warm summer days slipped into chilly late autumn, walnuts dropped from the orchard trees. The nuts spent winter drying in the lath house and those not carried away by the squirrels made their way inside for shelling, sorting and storing. I believe calling it merely spring cleaning would be to understate the energy and enthusiasm poured into lath house purification. All furniture was removed as walls were swept clean and spiders left homeless. The tangle of vines and webs and crunchy fall leaves trapped between them was removed from the lattice. Debris was broomed from the roof, the concrete floor mopped and rinsed with the hose. The table and benches were scoured before being returned to the lath house.

I believe calling it merely spring cleaning would be to understate the energy and enthusiasm poured into lath house purification. All furniture was removed as walls were swept clean and spiders left homeless. The tangle of vines and webs and crunchy fall leaves trapped between them was removed from the lattice. Debris was broomed from the roof, the concrete floor mopped and rinsed with the hose. The table and benches were scoured before being returned to the lath house. grandchildren were much actual help. I wasn’t. The idea that soon the table would be covered with lively print oil cloth and set for a family meal invited excitement on par with Christmas dinner. Memory of summers before, Grandma emerging from the back door and down the steps with a platter piled high with steaming

grandchildren were much actual help. I wasn’t. The idea that soon the table would be covered with lively print oil cloth and set for a family meal invited excitement on par with Christmas dinner. Memory of summers before, Grandma emerging from the back door and down the steps with a platter piled high with steaming  The lath house no longer stands behind the home on Myrtle Street. A snoop on Google Earth revealed it’s been replaced by a Victorian-type gazebo. In my dreams I buy the little bungalow back for our family, my brothers and me, our children and grandchildren; we erase all evidence that it ever slipped from our hands, or that time has passed. There the lath house stands tall, awaiting the spring flurry that brought summer and stories of clinking glasses, shouts of

The lath house no longer stands behind the home on Myrtle Street. A snoop on Google Earth revealed it’s been replaced by a Victorian-type gazebo. In my dreams I buy the little bungalow back for our family, my brothers and me, our children and grandchildren; we erase all evidence that it ever slipped from our hands, or that time has passed. There the lath house stands tall, awaiting the spring flurry that brought summer and stories of clinking glasses, shouts of

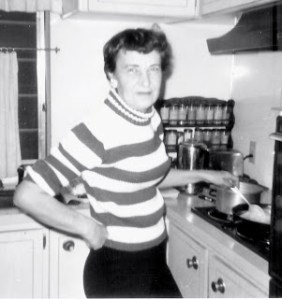

Peanut butter sandwiches with Olallieberry jam and a little mac salad on the side. Daily lunch when staying with my grandparents during the hot summers in Santa Rosa.

Peanut butter sandwiches with Olallieberry jam and a little mac salad on the side. Daily lunch when staying with my grandparents during the hot summers in Santa Rosa.

Just like her. A free spirit and free-thinker in a generation unfamiliar with and unwelcoming to either quality in women, as if it weren’t difficult enough to be Jewish and raised in an orphanage. Or, maybe because of.

Just like her. A free spirit and free-thinker in a generation unfamiliar with and unwelcoming to either quality in women, as if it weren’t difficult enough to be Jewish and raised in an orphanage. Or, maybe because of. Cooking School. Then I found a recipe in a McCall’s cookbook I’d been given in 1975 by my cousin, Eva. “Fresh Berry Pie”.

Cooking School. Then I found a recipe in a McCall’s cookbook I’d been given in 1975 by my cousin, Eva. “Fresh Berry Pie”. I knew. I could taste it. Dimension, another layer of flavor, depth without sweetness. Unexpected. In a berry pie, or in the cookbook falling apart high up on the shelf in my kitchen cabinet.

I knew. I could taste it. Dimension, another layer of flavor, depth without sweetness. Unexpected. In a berry pie, or in the cookbook falling apart high up on the shelf in my kitchen cabinet. cool? Did I remember to slide a little

cool? Did I remember to slide a little  Right out of a 1950’s diner. Lava-like juices had bubbled through the lattice and cooled around the rim to a shiny, luscious deep purple. Flaky barely sweet pie crust, each bite filled with Olallieberry goodness.

Right out of a 1950’s diner. Lava-like juices had bubbled through the lattice and cooled around the rim to a shiny, luscious deep purple. Flaky barely sweet pie crust, each bite filled with Olallieberry goodness.

ancient, tiny nun. I described all that had happened the day before. I had some fearsome faith back in the day. I probably thought she could pull up some Catholic mojo and make my grandmother better. I could barely get the words out to explain what I knew, what would be the undoing of my little family. Fanny was the light at the center of everything.

ancient, tiny nun. I described all that had happened the day before. I had some fearsome faith back in the day. I probably thought she could pull up some Catholic mojo and make my grandmother better. I could barely get the words out to explain what I knew, what would be the undoing of my little family. Fanny was the light at the center of everything.

That first Christmas came three weeks after her death. I prayed even harder to the baby Jesus tucked in his tiny manger under the watchful eyes of His parents, nestled in the crisp white sheet at the bottom of our Christmas tree. With twinkling lights and shimmering tinsel, ornaments reflecting its surrounds, our tree stood tall and alone in the corner of our living room. Each evening in the quiet before bed I knelt before the tree. I prayed to atone for Fanny’s death. I hadn’t been good enough in God’s eyes to save her.

That first Christmas came three weeks after her death. I prayed even harder to the baby Jesus tucked in his tiny manger under the watchful eyes of His parents, nestled in the crisp white sheet at the bottom of our Christmas tree. With twinkling lights and shimmering tinsel, ornaments reflecting its surrounds, our tree stood tall and alone in the corner of our living room. Each evening in the quiet before bed I knelt before the tree. I prayed to atone for Fanny’s death. I hadn’t been good enough in God’s eyes to save her. operated believing I wasn’t good enough. The ultimate judgment had been rendered and a life was lost. I saw it all in the rearview mirror and was shocked by the depth of the belief, the decision made as young girl based on a teacher’s words.

operated believing I wasn’t good enough. The ultimate judgment had been rendered and a life was lost. I saw it all in the rearview mirror and was shocked by the depth of the belief, the decision made as young girl based on a teacher’s words.

Hard leather soles make an unmistakable sound scuffling across an old wood floor. There’s a sharp clunk if the back slides off the heel and a little shuffling sound, because slippers are often extra roomy. My grandfather’s were.

Hard leather soles make an unmistakable sound scuffling across an old wood floor. There’s a sharp clunk if the back slides off the heel and a little shuffling sound, because slippers are often extra roomy. My grandfather’s were.

Medaligia D’Oro.

Medaligia D’Oro. Scappa via

Scappa via American Social Club.

American Social Club. gas stove that still had a cubby for burning wood, and twirl her to him. He’d grab her in dance stance, and lead her around the kitchen floor while singing, Arrivederci, Roma. She resisted every step.

gas stove that still had a cubby for burning wood, and twirl her to him. He’d grab her in dance stance, and lead her around the kitchen floor while singing, Arrivederci, Roma. She resisted every step. He had a shock of red hair.

He had a shock of red hair. Because I was not nearly mature enough to hear that kind of wisdom and probably never had pondered the word ‘ethics’, I immediately reported his statement to my best friend with the closest impersonation of his oh-so-serious voice I could muster. We laughed uproariously restating the phrase often especially before embarking on any kind of shenanigan.

Because I was not nearly mature enough to hear that kind of wisdom and probably never had pondered the word ‘ethics’, I immediately reported his statement to my best friend with the closest impersonation of his oh-so-serious voice I could muster. We laughed uproariously restating the phrase often especially before embarking on any kind of shenanigan. And I think a country fractured by identity politics and hypocrisy mourns Senator John McCain precisely because he practiced ethical congruency with a rigour most don’t know exists let alone understand.

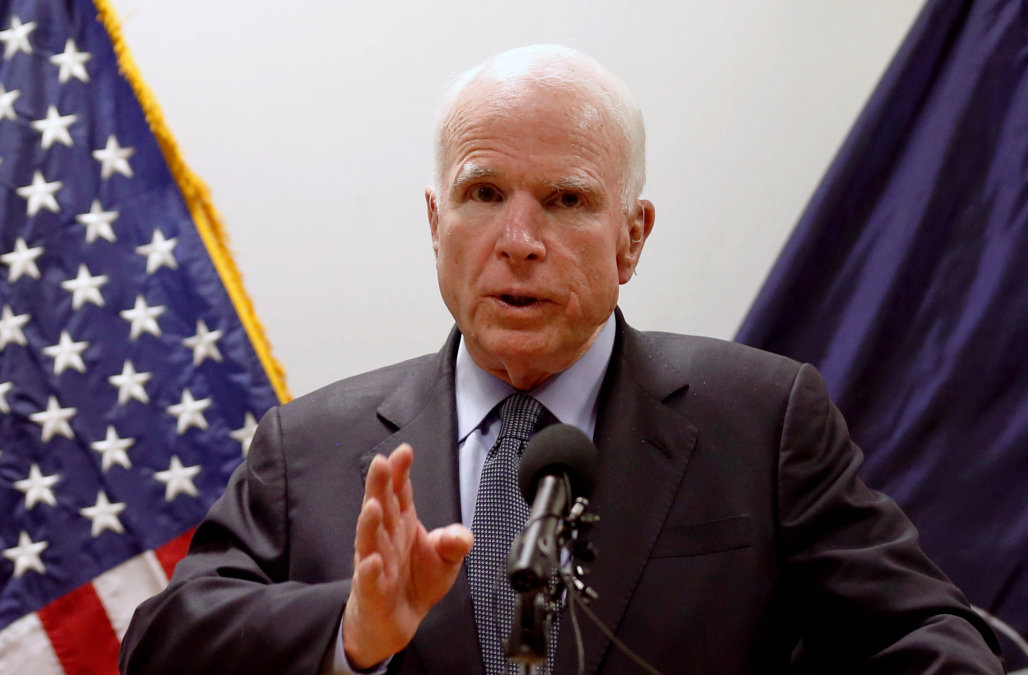

And I think a country fractured by identity politics and hypocrisy mourns Senator John McCain precisely because he practiced ethical congruency with a rigour most don’t know exists let alone understand.